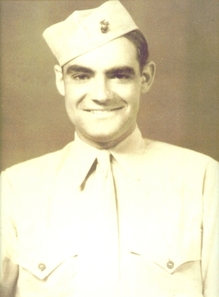

Elijah “Blackie” Pennington was born May 18, 1921, in Dew Drop, Kentucky, to Tom and Rosie Pennington. They were tobacco farmers in Elliot County, and Blackie and his brothers Hubert, Jesse, Troy, and Hysell, along with their sister, Mona, were raised in a log cabin until the “big” house was built. Tom Pennington was a tobacco farmer, blacksmith, carpenter, and maker of furniture and coffins. Blackie learned these crafts well at his father’s knee.

Blackie received only a third grade public school education, and his brother, Hubert, educated him through the sixth grade. Blackie had a deep, yearning desire to learn. He made a piece of furniture and sold it for money to buy an oil lamp, and did any odd job he could to earn money for the oil. He would beg or borrow any book he could lay his hands on, and read by the light of that oil lamp at night. He was a self taught expert on dozens of subjects, particularly the natural sciences. He was also an avid student of history.

Blackie left home at 17 to seek his fortune, and his fortune happened to end up in the Baltimore shipyards prior to World War II. He used to tell stories about working on the railroad, but we never could find out just what railroad or where he worked. He told many tales about the shipyards and he enjoyed that work. What he really wanted to be was a cook.

At the start of WWII, young men enlisted right and left or were drafted, and the shipyards lost their workers by the hundred-fold. So they hung on for dear life to any able bodied man who wanted to stay and work. Blackie stayed until he knew he was sure to be drafted into the Army and figured he probably should just go. He really did not want to be in the Army. He wanted to be a cook in the Marines. He reported to the Army induction station in Charleston, WVA, and stated his preference, but they did not care too much. He filled out the paperwork, and excused himself to go to the men’s room. As luck would have it, he ran into the Marine recruiter in there. He explained his dilemma to the recruiter, who said he would be delighted to have Blackie as a Marine recruit, but he would have to go into demolitions. Blackie thought anything was better than the Army, so he agreed. The Marine then explained to Blackie how he wasn’t looking very well and probably if he got really sick the Army might not want him anymore, and then proceeded to “help” Blackie “run” a fever, etc. Whatever those two pulled that day worked, because Blackie never went into the Army. He was inducted into the Marine Corp on 23 February 1943 and the rest is history.

Blackie loved the Marines from start to finish. He wanted the challenge, and he got it. He said they were the toughest men he had ever met in his life. He did his basic training at Camp Pendleton, CA, and then was stationed on Maui in Hawaii. He was as much of a practical joker then as he was up until he died, and a couple of his jokes, along with a couple of beers, got him a couple of nights in the brig a couple of times. He told of meeting Lee Marvin and getting into a fight with him. He said that Marvin was as tough then as he was on screen later. Blackie played poker and won as much as he lost, and sent the winnings home to his mother. He wrote her regularly and missed her terribly.

During this time, Blackie learned to be an expert demolitions specialist. He just naturally became an expert at anything he set his mind and hands to. There was a story of Blackie and his Marine buddies being harassed by a group of Army boys in Hawaii. The Army guys had a flower bed they were particularly proud of. Apparently they harassed him once too often, because one day he and his buddies boarded a half ton and drove it through the gate past the flower bed, lobbing explosives into the flower bed and thus bringing the Army down a notch or two. Yes, they got caught.

Blackie was deployed on a troop ship to the South Pacific. He saw action at Kwajalain in Feb 1944, Saipan in June 1944, Tinian in July 1944, and Iwo Jima in Feb 1945. He proved himself a hero on Tinian when he assumed the role of platoon sergeant when the group was lost. They dug in a foxhole for the night with Blackie on guard duty. He dozed off, and when he woke up they were surrounded by Japanese. Blackie had a flame-thrower, and many enemy met their maker that night. He received a citation for that action. The citation never meant as much to him as the respect and bond he and his men formed that night. They stayed in touch until Blackie died this year.

When he was mustered out of the Marines after the war, he was asked to go to Quantico to engineering school, possibly as an officer. His lack of education bothered him, though, and he turned it down. This was his greatest mistake, as he would have been one of the Corps’ best engineers. He went back to Kentucky, and his mother made him promise he would not go back into the service. He kept that promise and made his way to Ohio, where he opened the Buckeye Gardens with his brother, Troy.

Blackie met his wife, Alice, in 1946. They dated for five years, and during that time she actually waited tables at the Buckeye for him. She was stubborn and independent, much like he was. They had taken four blood tests to get their marriage license, and Alice backed out every time. On the fifth try, Blackie told her it was now or never. So they were married in Eaton, Ohio, on 12 June 1951. They had three children, Sherry, Steve, and Tom.

Blackie and Troy sold the Buckeye years later, and Blackie went full time into construction. He made his mark as a master carpenter and stone mason. He was well respected in his field and sought after by many construction companies.

Blackie joined the Masons and was raised as a Master Mason on 10 October 1981, joining the York Rite in 1982. He became a fully devoted member of the Whitewater Lodge and gave much of himself to it. He loved the Masons and the Marine Corps almost as much as he loved his family. In his mind there was not much difference, as he considered them all family.

After Alice passed away in 2001, Blackie spent his time buying and selling antiques and hunting garage sales with his close friend, Joy Weatherly. They spent many, many happy hours chasing down a bargain as Blackie loved a good deal. What he really loved about it was the opportunity to talk. He loved visiting and exchanging tales. When he died, dozens of oil lamps were found around his home, reminiscent of the oil lamp he read by when he was a kid in Kentucky, where he opened up his world through his books.

Blackie had many layers to him. He could be the gruff Marine, barking orders and showing little patience for laziness or foolishness. He could be the clown, telling the most ridiculous jokes you ever heard and playing practical jokes whenever he could get away with it. His dry sense of humor was legendary in his family. He loved to cook, and no one went hungry if he could help it. He could build solid, massive structures to last a hundred years, but could not operate the telephone answering machine at home.

He was the quiet guardian angel of his family, making sure everyone had enough groceries, keeping the oil changed in the girls’ cars, showing the boys how to use a pocket knife, giving out allowances so the kids would know how to handle money. His caring was not limited to his family. He often gave rides to hitchhikers and meals to the homeless. He never threw anything away that someone else could use. When he was working with a construction company in South Dakota one year, he saw a little Indian girl staring at a mirror like she had never seen one before. Blackie made sure she got that mirror. On the construction sites, when he was supervisor, he always hired the men in the most need of a job, making sure they got every penny coming to them and had rides to and from work. Many a young man found guidance from Blackie, into the Corps, the Masons, or just through life.

Written by Sherry Pennington

08/24/05

Blackie received only a third grade public school education, and his brother, Hubert, educated him through the sixth grade. Blackie had a deep, yearning desire to learn. He made a piece of furniture and sold it for money to buy an oil lamp, and did any odd job he could to earn money for the oil. He would beg or borrow any book he could lay his hands on, and read by the light of that oil lamp at night. He was a self taught expert on dozens of subjects, particularly the natural sciences. He was also an avid student of history.

Blackie left home at 17 to seek his fortune, and his fortune happened to end up in the Baltimore shipyards prior to World War II. He used to tell stories about working on the railroad, but we never could find out just what railroad or where he worked. He told many tales about the shipyards and he enjoyed that work. What he really wanted to be was a cook.

At the start of WWII, young men enlisted right and left or were drafted, and the shipyards lost their workers by the hundred-fold. So they hung on for dear life to any able bodied man who wanted to stay and work. Blackie stayed until he knew he was sure to be drafted into the Army and figured he probably should just go. He really did not want to be in the Army. He wanted to be a cook in the Marines. He reported to the Army induction station in Charleston, WVA, and stated his preference, but they did not care too much. He filled out the paperwork, and excused himself to go to the men’s room. As luck would have it, he ran into the Marine recruiter in there. He explained his dilemma to the recruiter, who said he would be delighted to have Blackie as a Marine recruit, but he would have to go into demolitions. Blackie thought anything was better than the Army, so he agreed. The Marine then explained to Blackie how he wasn’t looking very well and probably if he got really sick the Army might not want him anymore, and then proceeded to “help” Blackie “run” a fever, etc. Whatever those two pulled that day worked, because Blackie never went into the Army. He was inducted into the Marine Corp on 23 February 1943 and the rest is history.

Blackie loved the Marines from start to finish. He wanted the challenge, and he got it. He said they were the toughest men he had ever met in his life. He did his basic training at Camp Pendleton, CA, and then was stationed on Maui in Hawaii. He was as much of a practical joker then as he was up until he died, and a couple of his jokes, along with a couple of beers, got him a couple of nights in the brig a couple of times. He told of meeting Lee Marvin and getting into a fight with him. He said that Marvin was as tough then as he was on screen later. Blackie played poker and won as much as he lost, and sent the winnings home to his mother. He wrote her regularly and missed her terribly.

During this time, Blackie learned to be an expert demolitions specialist. He just naturally became an expert at anything he set his mind and hands to. There was a story of Blackie and his Marine buddies being harassed by a group of Army boys in Hawaii. The Army guys had a flower bed they were particularly proud of. Apparently they harassed him once too often, because one day he and his buddies boarded a half ton and drove it through the gate past the flower bed, lobbing explosives into the flower bed and thus bringing the Army down a notch or two. Yes, they got caught.

Blackie was deployed on a troop ship to the South Pacific. He saw action at Kwajalain in Feb 1944, Saipan in June 1944, Tinian in July 1944, and Iwo Jima in Feb 1945. He proved himself a hero on Tinian when he assumed the role of platoon sergeant when the group was lost. They dug in a foxhole for the night with Blackie on guard duty. He dozed off, and when he woke up they were surrounded by Japanese. Blackie had a flame-thrower, and many enemy met their maker that night. He received a citation for that action. The citation never meant as much to him as the respect and bond he and his men formed that night. They stayed in touch until Blackie died this year.

When he was mustered out of the Marines after the war, he was asked to go to Quantico to engineering school, possibly as an officer. His lack of education bothered him, though, and he turned it down. This was his greatest mistake, as he would have been one of the Corps’ best engineers. He went back to Kentucky, and his mother made him promise he would not go back into the service. He kept that promise and made his way to Ohio, where he opened the Buckeye Gardens with his brother, Troy.

Blackie met his wife, Alice, in 1946. They dated for five years, and during that time she actually waited tables at the Buckeye for him. She was stubborn and independent, much like he was. They had taken four blood tests to get their marriage license, and Alice backed out every time. On the fifth try, Blackie told her it was now or never. So they were married in Eaton, Ohio, on 12 June 1951. They had three children, Sherry, Steve, and Tom.

Blackie and Troy sold the Buckeye years later, and Blackie went full time into construction. He made his mark as a master carpenter and stone mason. He was well respected in his field and sought after by many construction companies.

Blackie joined the Masons and was raised as a Master Mason on 10 October 1981, joining the York Rite in 1982. He became a fully devoted member of the Whitewater Lodge and gave much of himself to it. He loved the Masons and the Marine Corps almost as much as he loved his family. In his mind there was not much difference, as he considered them all family.

After Alice passed away in 2001, Blackie spent his time buying and selling antiques and hunting garage sales with his close friend, Joy Weatherly. They spent many, many happy hours chasing down a bargain as Blackie loved a good deal. What he really loved about it was the opportunity to talk. He loved visiting and exchanging tales. When he died, dozens of oil lamps were found around his home, reminiscent of the oil lamp he read by when he was a kid in Kentucky, where he opened up his world through his books.

Blackie had many layers to him. He could be the gruff Marine, barking orders and showing little patience for laziness or foolishness. He could be the clown, telling the most ridiculous jokes you ever heard and playing practical jokes whenever he could get away with it. His dry sense of humor was legendary in his family. He loved to cook, and no one went hungry if he could help it. He could build solid, massive structures to last a hundred years, but could not operate the telephone answering machine at home.

He was the quiet guardian angel of his family, making sure everyone had enough groceries, keeping the oil changed in the girls’ cars, showing the boys how to use a pocket knife, giving out allowances so the kids would know how to handle money. His caring was not limited to his family. He often gave rides to hitchhikers and meals to the homeless. He never threw anything away that someone else could use. When he was working with a construction company in South Dakota one year, he saw a little Indian girl staring at a mirror like she had never seen one before. Blackie made sure she got that mirror. On the construction sites, when he was supervisor, he always hired the men in the most need of a job, making sure they got every penny coming to them and had rides to and from work. Many a young man found guidance from Blackie, into the Corps, the Masons, or just through life.

Written by Sherry Pennington

08/24/05